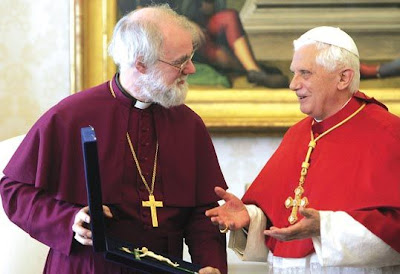

Ratzinger and Rowan - An Uncommon Amalgam

BB NOTE: The Pope comes to Britain next week. It is well-known that there are differences between them, but the Tablet takes a closer look and finds some surprising things in common. First up: St. Augustine.

From here:

Rowan Williams, like Joseph Ratzinger, is a deep-dyed Augustinian, which explains among other things his very developed social conscience, and the prophetic though sometimes unduly anguished tone of his pronouncements on politics and society.

Just before the turn of the millennium, Ratzinger gave an extended interview to Peter Seewald, a German journalist and lapsed Catholic who later returned to the faith under the then cardinal’s influence. When asked by Seewald how many paths to God there are, Ratzinger replied unhesitatingly that there are as many paths as human beings. If he were only allowed to take one book to a desert island besides the Bible and Augustine’s autobiographical Confessions, he said that he would choose Hermann Hesse’s Buddhist-inspired novella Siddhartha – an old hippy favourite.

To speak of the Augustinian influence on Ratzinger and Williams in terms of pessimism about human nature is to short-change Augustine, as well as his two admirers. Archbishop and Pope are in different ways associated with a recovery of nerve in Christian thought over recent decades, and here, too, Augustine has supplied both men with some of the themes on which their writings are variations.

A stripped-down account of the saint’s legacy might draw out the emphasis he gives to heart, as well as mind, in human understanding, and his conviction that faith and reason are complementary elements in our mental make-ups. Frustrated in different ways by perceived shortcomings in their theological education, both men absorbed the Confessions in their youth, later describing the experience as seismic. The influence of Augustine is clear throughout Ratzinger’s Introduction to Christianity, which contains many a put-down to the unexamined assumptions behind “empiricist” attacks on the coherence of religion. Early on, for example, we read that “knowledge of the functional aspect of the world, as procured for us so splendidly by present-day technical and scientific thinking, brings with it no understanding of the world and of being. Understanding grows only out of belief.” Richard Dawkins take note.

The similarities between Joseph Ratzinger and Rowan Williams extend beyond their theological formations. “I have two things in common with the Holy Father,” quipped the archbishop in a recent speech. “One is a love of cats; the other a hospitable instinct towards Anglican clergy” – the second of these being the mildest of digs at Rome’s recent proposal on so-called ordinariates for Anglican trad itionalists considering a change of church allegiance. To this might be added a shared depth of spirituality, and a mutual love of good liturgy and ceremonial.

As the comment just quoted indicates, the archbishop also has a sense of humour – as does the Pope. In his days as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Cardinal Ratzinger would sometimes tell visitors to his office that “we shall shortly be seeing what the Holy Father has to say” on this or that topic. He was speaking with a twinkle in his eye. The statement concerned would invariably have been written by himself.

Do the intellectual formations of the two men tell us more about their policies as leaders? Yes and no. Williams’ recent trajectory has more to do with his instincts as an Anglo-Catholic, than his devotion to Augustine. But for all he has suffered in recent years, especially through the threats of schism orchestrated by conservatives in the United States and Africa, Rowan Williams still prizes the distinctive witness of Anglicanism, including its far more open forms of government, and has a very direct answer – “Because I don’t believe the Pope is infallible” – to the question of why he didn’t become a Catholic in his youth.

After an acutely difficult early period at Lambeth, he won respect from both the liberal and conservative wings of his Communion and went on to make a success of the 2008 Lambeth Conference. His record compares favourably with that of Benedict, who began his reign five years ago with some bridge-building gestures (particularly through meeting Hans Küng, one of his most dogged liberal critics), but has gone on to display pro-conservative partisanship in other respects, and an unwillingness to face up to what the child-abuse scandal implies about the need for greater transparency in church life.

Observers agree that their relationship is unusually good, extending well beyond the staple courtesies shown by John Paul II towards Robert Runcie and George Carey. Dr Williams read several of the Pope’s books in German before meeting Benedict for the first time in 2005. The following year, the archbishop was extended the unusual honour of being invited to lunch with the Pope. This encounter was scheduled to last for an hour: in the event it went on for three times that long. Dr Williams has never revealed what was discussed, other than that the Pope asked about the effect of women’s ordin ation on the Church of England. We can safely assume that the table talk was also heavily theological.

Later on the same day, the archbishop gave a meaty lecture entitled “Secularism, Faith and Freedom” at the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, which defended the legitimacy of public expressions of religion. The address was released on DVD shortly afterwards. I am told by a reliable source that the Pope watched it four times. Then, when the two met in Naples in 2008, the Pope said “now I’m going to see my friend, Rowan” in the hearing of Bishop John Flack, at that time director of the Anglican Centre in Rome.

The warmth betokened by these anecdotes has not yet paid large dividends. Formal ecumenical progress has been glacial over the past two decades, even though the theological quality of debate between the two Churches has risen steadily, and relations between the archbishop and Cardinal Walter Kasper, president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, are especially close. As indicated, Rowan Williams has endured the searing effects of what are seen by the Catholic and Orthodox Churches as unilateral reforms introduced by some parts of the Anglican Communion without a critical mass of broader support.

But can the Pope, insistent as he is on his role as custodian of the faith, also give due weight to the notion that doctrine develops? He remains nervous about the subject – but paradoxically so, since development is a characteristically Catholic idea. What is more, the beatification of Cardinal Newman forms one of the chief objects of Benedict’s forthcoming visit to Britain.

Read it all here.

From here:

Rowan Williams, like Joseph Ratzinger, is a deep-dyed Augustinian, which explains among other things his very developed social conscience, and the prophetic though sometimes unduly anguished tone of his pronouncements on politics and society.

Just before the turn of the millennium, Ratzinger gave an extended interview to Peter Seewald, a German journalist and lapsed Catholic who later returned to the faith under the then cardinal’s influence. When asked by Seewald how many paths to God there are, Ratzinger replied unhesitatingly that there are as many paths as human beings. If he were only allowed to take one book to a desert island besides the Bible and Augustine’s autobiographical Confessions, he said that he would choose Hermann Hesse’s Buddhist-inspired novella Siddhartha – an old hippy favourite.

To speak of the Augustinian influence on Ratzinger and Williams in terms of pessimism about human nature is to short-change Augustine, as well as his two admirers. Archbishop and Pope are in different ways associated with a recovery of nerve in Christian thought over recent decades, and here, too, Augustine has supplied both men with some of the themes on which their writings are variations.

A stripped-down account of the saint’s legacy might draw out the emphasis he gives to heart, as well as mind, in human understanding, and his conviction that faith and reason are complementary elements in our mental make-ups. Frustrated in different ways by perceived shortcomings in their theological education, both men absorbed the Confessions in their youth, later describing the experience as seismic. The influence of Augustine is clear throughout Ratzinger’s Introduction to Christianity, which contains many a put-down to the unexamined assumptions behind “empiricist” attacks on the coherence of religion. Early on, for example, we read that “knowledge of the functional aspect of the world, as procured for us so splendidly by present-day technical and scientific thinking, brings with it no understanding of the world and of being. Understanding grows only out of belief.” Richard Dawkins take note.

The similarities between Joseph Ratzinger and Rowan Williams extend beyond their theological formations. “I have two things in common with the Holy Father,” quipped the archbishop in a recent speech. “One is a love of cats; the other a hospitable instinct towards Anglican clergy” – the second of these being the mildest of digs at Rome’s recent proposal on so-called ordinariates for Anglican trad itionalists considering a change of church allegiance. To this might be added a shared depth of spirituality, and a mutual love of good liturgy and ceremonial.

As the comment just quoted indicates, the archbishop also has a sense of humour – as does the Pope. In his days as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Cardinal Ratzinger would sometimes tell visitors to his office that “we shall shortly be seeing what the Holy Father has to say” on this or that topic. He was speaking with a twinkle in his eye. The statement concerned would invariably have been written by himself.

Do the intellectual formations of the two men tell us more about their policies as leaders? Yes and no. Williams’ recent trajectory has more to do with his instincts as an Anglo-Catholic, than his devotion to Augustine. But for all he has suffered in recent years, especially through the threats of schism orchestrated by conservatives in the United States and Africa, Rowan Williams still prizes the distinctive witness of Anglicanism, including its far more open forms of government, and has a very direct answer – “Because I don’t believe the Pope is infallible” – to the question of why he didn’t become a Catholic in his youth.

After an acutely difficult early period at Lambeth, he won respect from both the liberal and conservative wings of his Communion and went on to make a success of the 2008 Lambeth Conference. His record compares favourably with that of Benedict, who began his reign five years ago with some bridge-building gestures (particularly through meeting Hans Küng, one of his most dogged liberal critics), but has gone on to display pro-conservative partisanship in other respects, and an unwillingness to face up to what the child-abuse scandal implies about the need for greater transparency in church life.

Observers agree that their relationship is unusually good, extending well beyond the staple courtesies shown by John Paul II towards Robert Runcie and George Carey. Dr Williams read several of the Pope’s books in German before meeting Benedict for the first time in 2005. The following year, the archbishop was extended the unusual honour of being invited to lunch with the Pope. This encounter was scheduled to last for an hour: in the event it went on for three times that long. Dr Williams has never revealed what was discussed, other than that the Pope asked about the effect of women’s ordin ation on the Church of England. We can safely assume that the table talk was also heavily theological.

Later on the same day, the archbishop gave a meaty lecture entitled “Secularism, Faith and Freedom” at the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, which defended the legitimacy of public expressions of religion. The address was released on DVD shortly afterwards. I am told by a reliable source that the Pope watched it four times. Then, when the two met in Naples in 2008, the Pope said “now I’m going to see my friend, Rowan” in the hearing of Bishop John Flack, at that time director of the Anglican Centre in Rome.

The warmth betokened by these anecdotes has not yet paid large dividends. Formal ecumenical progress has been glacial over the past two decades, even though the theological quality of debate between the two Churches has risen steadily, and relations between the archbishop and Cardinal Walter Kasper, president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, are especially close. As indicated, Rowan Williams has endured the searing effects of what are seen by the Catholic and Orthodox Churches as unilateral reforms introduced by some parts of the Anglican Communion without a critical mass of broader support.

But can the Pope, insistent as he is on his role as custodian of the faith, also give due weight to the notion that doctrine develops? He remains nervous about the subject – but paradoxically so, since development is a characteristically Catholic idea. What is more, the beatification of Cardinal Newman forms one of the chief objects of Benedict’s forthcoming visit to Britain.

Read it all here.

No comments:

Post a Comment